Behind the Image: Afloat

I started talking, half-jokingly, about trying to isolate an iceberg, which I know wouldn't be an easy task. But Jesse is always super keen to make my ideas come to life. He suggested that we could isolate an iceberg through a mix of towing and paddling. But, all we had for paddling was a hiking pole. As for towing, he suggested that he could place an ice screw into an iceberg, tie that to a rope and then we would be able to tow it from shore.

This image was taken during a mountaineering trip to the Mons Icefield, which is a sizeable area of ice on the divine (half in Banff National Park, Alberta, half in British Columbia). Mountaineering was the main purpose of the trip, but like all trips I like to take the opportunity for some photography. We spent three days making several ascents in the vicinity of the lake you see in the shot. And of course, we had vantage points of that lake from various summits around it.

We thought if there was time after we summited the various peaks we would just go chill by the lake, relax a bit and see if we could get creative with the camera. So, after our sixth ascent, it was early afternoon and we decided to stop by the lake on our way back to Mons Hut. There wasn’t anything specific I had in mind, but I absolutely love to photograph ice. When you have icebergs, mountains and glaciers, and you mix all that together with a model as keen as Jesse, you have all the ingredients to get something pretty cool (despite the harsh light conditions!).

We shot a variety of ideas involving Jesse and Mons Peak in the background and the lake and the icebergs. But I thought it would be cool to create an image where Jesse would be adrift on an iceberg, partly because I like those types of shots that are a little bit puzzling for the audience. Also, I have a pretty large collection of images of people stranded on little islands or icebergs.

I also wanted to create an image that leaves something to interpretation. In this case, that’s a vague commentary on the changes in the climate and glaciers and the way humans are impacted by that. Perhaps we are unknowingly (and in some ways knowingly) drifting into uncharted territory, on the world’s last little piece of ice. Or maybe the person is so engrossed in what they are doing that they didn’t notice winter had run out.

The lake itself is a feature that’s temporary, which makes it all the more exciting to work with.

As far as this specific image is concerned, the icebergs were plentiful but the wind had piled them all up together at one end of the like. It was quite a cluttered scene. My main concern right away from a composition standpoint was trying to simplify the scene.

I started talking, half-jokingly, about trying to isolate an iceberg, which I know wouldn't be an easy task. But Jesse is always super keen to make my ideas come to life. He suggested that we could isolate an iceberg through a mix of towing and paddling. But, all we had for paddling was a hiking pole. As for towing, he suggested that he could place an ice screw into an iceberg, tie that to a rope and then we would be able to tow it from shore.

So we tried to find a piece of ice and what transpired after was pretty comical. First, we needed a piece that was not too big, not too small. If it was too big it would snag on the bottom of the lake all the time. If it was too small, it wouldn’t support Jesse’s weight. We also needed to find an iceberg that Jesse could get onto from the shore somewhat easily.

So Jesse got on there and then through a mix of towing and paddling (and you'll see that in the behind-the-scenes), he eventually managed to drift away from the other icebergs, therefore simplifying the scene quite a bit.

I had Mons Peak and lots of ice, which was a prominent background. So I wanted to make Jesse pretty small to convey the scale. I opted to shoot from a little higher up the bank, a little bit further from Jesse, and with a bit of a wider lens. I didn’t want to go too wide so that the background would still be quite prominent. When you shoot too wide, the mountains get very, very small and you lose that feeling of awe in the shots.

I placed Jesse right in the middle to align with Mons Peak. He kept drifting around so it was up to me to travel up and down the shore to try to keep him aligned. And then we tried a variety of body positions.

I shot lots of variations of this image but this was the short I liked the best. In the end, I felt that it conveyed the vision that I'd had on the shore prior to messing with the icebergs. And I thought it was a unique image of a feature that probably won't exist for very much longer.

Eventually, after a few attempts, Jesse managed to tie his hiking pole to the rope that he had with him, then threw his hiking pole onto the shore to a location where I was able to grab it. I pulled him back home to wrap up a little creative — and comical — session.

Settings:

Canon R5

Canon 15-35mm

f/2.8 lens

f/16

ISO 400 1/200s

Documenting Vanishing Ice: Q+A with Paul Zizka

I’ve been photographing ice since the very early stages of my career. Whether glaciers, ice caves, frozen lakes, or mountaintops, I would continuously find myself drawn to cold landscapes in search of ice in its many forms, textures, and hues. Icescapes are among the most dynamic, visually exciting, and rewarding places a photographer can document. But as I spent more time shooting ice, it became apparent that I was capturing something that is vanishing.

I’ve been photographing ice since the very early stages of my career. Whether glaciers, ice caves, frozen lakes, or mountaintops, I would continuously find myself drawn to cold landscapes in search of ice in its many forms, textures, and hues. Icescapes are among the most dynamic, visually exciting, and rewarding places a photographer can document. But as I spent more time shooting ice, it became apparent that I was capturing something that is vanishing.

As global temperatures rise, we risk the melting of our polar regions and glaciers. Beyond the long-term human and environmental consequences of melting ice, the loss of these frozen landscapes also signifies the loss of a unique and powerful experience. I realized that my calling as an artist is to document and celebrate ice before it disappears. It’s my responsibility to bring the beauty and mystery of these foreign, enchanting worlds to as many people as possible.

This realization led to the launch of my latest project, Cryophilia.

This project has been met with support, positivity, and much curiosity, so I thought I’d take the opportunity to answer some frequently asked questions.

1. What is Cryophilia?

Cryophilia is an effort to document the rapid changes in glaciers and to celebrate the beauty of glacial ice in Canada and around the globe.

2. How/when did the Cryophilia project start and how did it get its name?

“Cryophilia” comes from ancient Greek meaning “frost loving.” Cryophiles prefer or thrive at low temperatures. I’ve always been drawn to photographing ice, cold places, and the high latitudes and have spent countless hours documenting glaciers ever since I started my journey as a photographer. Cryophilia is a personal commitment to investing a lot of my time and energy as an artist over the next several years to bring to light the changes that are happening in glacial environments and also the incredible beauty of these inhospitable locations.

3. What does the next phase of this project look like?

Over the next few years, I plan to focus a vast portion of my attention and efforts on collecting images from glacial environments, both here at home in the Canadian Rockies and abroad, and bring the photographs to the world. I believe photography has the power to stir up emotion, generate awareness and incite change when other means of communication fail. Eventually, my hope is to convey my findings in a cohesive way through the creation of a book and the presentation of an exhibit.

Ice cave explorations in the Canadian Rockies.

4. What is it about ice that intrigues and inspires you so much as an artist?

For one, there are the aesthetics: I never cease to be amazed by the multitude of shapes, forms, colours and textures a simple compound like ice can display. The possibilities appear infinite. As an artist, I find that ice renews itself and presents itself differently on every new exploration, which keeps the creative process exciting.

The other reason I am fascinated by ice, particularly glacier ice, is that it is becoming rarer, more precious — and it is becoming so at an alarming rate. The changes happening in glaciers worldwide warrant me to document them with urgency. Photography is the perfect medium to record what is occurring in these extremely dynamic environments.

5. What are some of the challenges that this project poses?

Accessing glaciers takes time, and so I expect time to be one of the key limiting factors in this project will be finding the time to visit those places repeatedly. Glaciated areas are characterised by the likelihood of inclement weather, which can make the photography process tedious at times.

6. What are you learning from this project?

I am more and more aware of how fast the ice is vanishing, and of the ramifications of that loss. Beyond the long-term human and environmental consequences of melting ice, for me the loss of these frozen landscapes also signifies the loss of a unique, powerful experience. The stillness and silence of cold places are humbling and wonderfully eerie; they are among some of the most magical on Earth.

7. What do you hope other people learn or consider when they encounter your project?

I sincerely hope that people develop an appreciation for how special, stunning and unique these environments are, and also how fast they are vanishing, on a timescale that we can relate to.

“Icicle Hollow” - Banff National Park, 2022.

8. Tell us the story behind one of the limited edition images in your growing Cryophilia collection.

The above photograph is an example of the fleeting, fascinating features I regularly come across on my visits to the local glaciers. I spotted a small opening in a cornice while wandering along the edge of the Columbia Icefield, and allowed my curiosity to get the best of me. Upon closer inspection, the hole opened onto a small, but stunning crystalline chamber within the glacier. At the end of the room, icicles dangled from the ceiling, shining brightly against the blue walls beyond. Those are beautiful, intricate features that only exist for a few days at most, and they are findings I enjoy sharing with the world, in the hope that they elicit a response to care for these places.

9. How can people support this project and your mission?

I encourage people to look at the images and let themselves be amazed by the diversity, dynamism, and beauty of those underdocumented environments. Let me know how the images make you feel. And develop an appreciation for glacial environments.

Keep following the project:

Official Cryophilia page: https://www.zizka.ca/cryophilia

Project News: https://mailchi.mp/zizka/cryophilia

Greenland Grandeur: Ice, Water and Northern Lights

Earlier this year, I was fortunate to spend an entire month in Greenland, a place that feels like my second home. This trip, which marked my 6th visit to the island country known as Kalaallit Nunaat in Greenlandic and Grønland in Danish, involved leading two OFFBEAT photography workshops in familiar locations and working on a tourism photography project at a destination that was new to me. Despite revisiting several places, natural wonders such as ice, water, and northern lights made each experience unique.

Earlier this year, I was fortunate to spend an entire month in Greenland, a place that feels like my second home. This trip, which marked my 6th visit to the island country known as Kalaallit Nunaat in Greenlandic and Grønland in Danish, involved leading two OFFBEAT photography workshops in familiar locations and working on a tourism photography project at a destination that was new to me. Despite revisiting several places, natural wonders such as ice, water, and northern lights made each experience unique.

I arrived in Ilulissat for the first edition of the Greenland Grandeur workshop alongside fellow trip leaders Curtis Jones and Stephen DesRoches. We had each made numerous trips there and all agreed that we had never seen so much ice there before. Considering the recent launch of my Cryophilia project, which revolves around documenting disappearing glaciers and ice, I was excited for the photo possibilities. I was also thrilled for the participants who arrived a few days after we did.

During the first half of the workshop, we focused our attention on the sea ice in the fjords of Ilulissat and were treated to an incredible aurora display. We then took a ferry to Disko Island, where we photographed black sand beaches and Kuannit, my favourite stretch of coastline in the world. Foul weather sent us back to Ilulissat early, but the consolation prize was documenting more incredible ice formations around Ilulissat.

Gargantuan ice formations off the coast of Greenland.

The second workshop brought lots of familiar faces to Greenland. Participants were treated to an incredible aurora display upon arrival, before the workshop had officially started. With a wide spectrum of colours filling the sky, it was possibly the best aurora display of the entire month. The workshop program mirrored the first and it mostly went according to plan; the only curveball was that during our stay on Disko Island, Greenland got the biggest rain event it’s seen in over 40 years.

We may have been damp but we kept our spirits high and continued getting out regardless of the downpour. When the weather does unexpected things, it also leads to unexpected photo ops. We witnessed some beautiful things including the area’s waterfalls flowing at ten times the volume and unusual chocolate-coloured water flowing onto the beach and into the iceberg-laden sea. We made the most of it before heading back to Ilulissat to wrap up the program.

A rare combination: chocolate-coloured waves and a black sand beach.

Curtis, Stephen and I stayed on for a few extra days. We called this period “play time” but we are actually heading to Maniitsoq in western Greenland on an assignment for Destination Arctic Circle and Visit Greenland. We were thrilled to explore a place that none of us had seen before, especially since the few photos of Maniitsoq we could find were oozing with potential. Although harsh weather caused travel delays that cut our play time in half, we decided to head to Maniitsoq anyway. We were greeted by Ole from Maniitsoq Adventure Tours who sailed us to Inussuit Tasersuat, a narrow lake flanked by steep mountain ranges known as “The Great Lake of Giants”.

The instant we laid eyes on Inussuit Tasersuat, we unanimously agreed it was one of the most beautiful places we had ever seen. I was so blown away by the possibilities, I didn’t know where to start. It was one of the most epic places I’d ever seen and I wanted to do it justice by conveying that ‘wow factor’. We got to work right away and shot the lake from a variety of angles in diverse conditions. We shot it by day and night, from land and underwater, with a drone and even from kayaks provided by Ole. We even witnessed the aurora shimmering high above the landscape, but for me, the highlight was doing a full traverse of the lake in a kayak on a calm morning surrounded by towering peaks, glaciers, and their reflections. Inussuit Tasersuat is one of the most naturally beautiful places I’ve ever come across and I hope I’ll be lucky enough to return there one day.

Inussuit Tasersuat, also known as “The Great Lake of Giants”.

Both workshops and our playtime unfolded in phenomenal landscapes. Photographs allow me to share the majesty of these scenes, but they don’t convey the meaningful conversations we shared with the locals we encountered. Considering that three quarters of Greenland is covered by the only permanent ice sheet that exists outside Antarctica, I asked locals like Ole and our boat drivers about the changes to the ice that they’ve witnessed in their lifetimes. They all told us that the glaciers are receding at an alarming and unprecedented rate. Hearing this underscored what a privilege it is to be able to see and document that ice before it disappears. I hope you enjoy these images, but most of all, I hope they spark your curiosity about our planet’s vanishing ice.

Ecuador: Capturing Vanishing Ice on the Equator

On a mission to document vanishing ice across the globe, I found myself in Ecuador back in February — a South American nation named for its position on the Equator. You may wonder why I’m chasing ice on the Equator, but Ecuador is home to Andean peaks towering up to 6,310 metres. It turns out that the country’s stratovolcanoes are home to a number of receding glaciers.

On a mission to document vanishing ice across the globe, I found myself in Ecuador back in February — a South American nation named for its position on the Equator. You may wonder why I’m chasing ice on the Equator, but Ecuador is home to Andean peaks towering up to 6,310 metres. It turns out that the country’s stratovolcanoes are home to a number of receding glaciers.

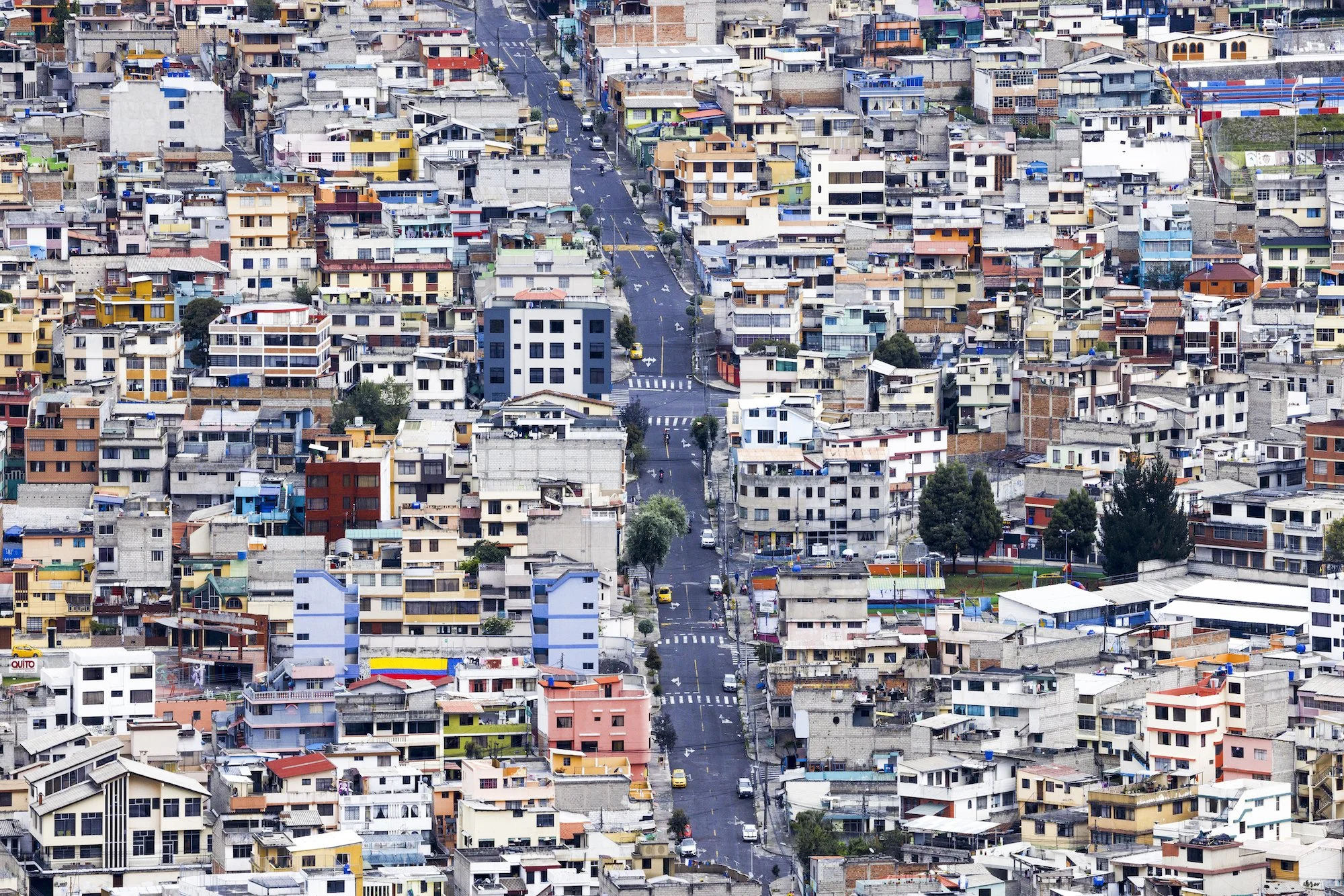

I arrived in Quito with a friend and fellow photographer, Kris Andres. An assault on all the senses, Quito was as colourful, bustling, and stimulating as I imagined. We hiked to the summit of Volcán Pichincha (4,800 m) to acclimatize for the higher elevations we planned to reach. Having spent time at elevation in Africa and Nepal, I acclimatized rather well.

Colourful and bustling Quito. Photo by Paul Zizka.

Quito is surrounded by hills and highlands, which we were eager to explore. It wasn’t long before we were en route to our next objective: Volcá Illiniza Norte (5,126 m). We set off around midnight in light snow, guided by the light of our headlamps. Conditions were challenging due to the build-up of ice and rime from the previous day’s storm. We couldn’t see anything when we reached the summit but just as we were about to pack up, everything opened up. It was absolute magic and everything I could wish for as a photographer: brilliant side light, dynamic clouds, and Illiniza Sur (5,245 m) rising in the background. In terms of scenery and photography, that fifteen minutes was the highlight of the entire trip.

Clouds parting momentarily on the summit of Volcan Illiniza Norte. Photo by Paul Zizka.

That’s not to say that the rest of our time in Ecuador wasn’t absolutely mind-blowing. Following Illiniza Norte, we hiked into the Jose Ribas refuge by circumventing the Quilotoa Crater. We spent half a day walking on the rim of a vast volcano, immersed in scenery that was unlike anything I’d ever seen before. Quilotoa is much older than the two previous volcanoes, geologically speaking. The landscape is also incredibly lush and vibrant. Traversing such different terrain was a refreshing intermission before our biggest climb.

Quilotoa Crater. Photo by Paul Zizka.

The pinnacle of our trip was Volcán Cotopaxi (5,897 m) located about 50 km south of Quito. We stayed at Tambo Paxi at the base of the volcano, got up to shoot the sunrise, then drove all the way up to a shelter that sits at an elevation of approximately 5000 metres. We got some rest but were up at 11 pm for a midnight start. With a new moon, we could only see as far ahead as our headlamps allowed. A billion stars glimmered overhead and Quito’s lights were visible in the distance. We wove our way through seracs towards the summit. Clouds rolled in halfway up, which was unfortunate for photos but added to the atmosphere.

We topped out on the edge of a giant summit crater. Eventually, other rope teams arrived at the summit of Cotopaxi. The clouds didn’t part until we were halfway down, revealing distant volcanoes and volcanic plains. The descent was magical and made for some great photo opportunities and some of my favourite images from the trip.

The Cotopaxi Refuge. Photo by Paul Zizka.

This trip to Ecuador was a wonderful opportunity for me to observe a new landscape, experience a new culture, and document rapidly changing glaciers that sit high up on the Equator. The trip came with its own challenges, like shooting in a highly dynamic environment that’s constantly changing. With volcanoes attracting and shedding weather quickly, I had to be on the ball to make the most of brief windows of opportunity. Overall, It was unbelievable to climb ice so close to the equator and gaze into distant coastal areas and jungles from a high altitude. The trip ultimately revealed that Ecuador is full of kind people and offers a ton of variety despite being such a small country. I certainly look forward to returning someday!

Weaving through seracs on our ascent of Cotopaxi. Photo by Paul Zizka.

Memories from Africa: Wildlife, Climbing and the Last Glaciers

A collection of my favourite images from a recent photography workshop and photo mission to capture the last ice in Botswana and Uganda.

After a long pause from leading workshops abroad, I was fortunate to embark on two trips in the latter half of 2021. The most recent was a journey to beautiful Botswana, a must-see for landscape and wildlife lovers alike. This particular adventure provided the best of both worlds; it began with an immersive OFFBEAT workshop experience and ended with a personal trip to document some of the only remaining ice on the African continent. Both resulted in memories I will cherish for a long time.

Breathless in Botswana

The workshop went marvellously well. We split our time between the Khwai Private Reserve of the Okavango Delta and Chobe National Park. We were fortunate to spot elephants, big cats, giraffes, hippos, baboons, and birds of many feathers. Since we could never predict which animals we would come across, each game drive and boat cruise provided a completely unique experience. Each of our participants went home with thousands of photographs of dozens of animals. For me, the most memorable encounters involved cheetahs, elephants, and lions bathing in magical African light.

One of Covid’s silver linings has been renewed appreciation. While I recognized the value of travel prior to the pandemic, it all felt a touch more special this time around. Whether gathering with old friends, meeting new faces, teaching again, drinking local coffee, or sitting quietly with a lion—it all seemed even more precious.

If you’ve never been to Botswana, you absolutely need to add it to your bucket list. Everything about this country, from its diverse landscapes and animals to its generous people, will leave you breathless.

A mother and baby elephant in Chobe National Park, Botswana. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

The Mountains of the Moon

After wrapping up the workshop, I embarked on a personal journey to find and photograph the last remnants of ice on the African continent. I chase ice because of its surreal beauty, its impact on the land and its people, and because it's so quickly disappearing. Chasing ice in Africa led me deep into the Rwenzori Mountains, located on the border between Botswana and Uganda. They are also known as the Mountains of the Moon.

Much of the multi-day trek was spent following our local guides through an otherworldly landscape of tropical plants and ancient rock shrouded by mist and rain. The highlight of the trip was the surreal summit day high on Mount Stanley. There I was in an extremely remote area, at one of the last remaining glaciers in Africa. I was sitting at 5,109 m above sea level in -20C temperatures and zero visibility with one butt cheek in Congo and the other in Uganda. I was there, in that quiet and sacred place, as news from the outside world trickled in: the Omicron variant was beginning to shut down travel to many African nations. It was a bizarre experience and an emotional rollercoaster.

You may think of glaciers when you think of Africa, but ice does exist there—for the time being. The now-tiny glaciers of that region have existed for a long, long time. They have had a massive impact on the land and the locals throughout history. They carved the valleys into what you see today and they provided water for life to fill those valleys. I chase ice because of its surreal beauty, its impact on the land and its people, and because it's so quickly disappearing. Embarking on this trip to see those glaciers in their terminal state was deeply moving and well-worth documenting for me.

The Rwenzori (also spelled Ruwenzori or Rwenjura) is a mountain range in eastern equatorial Africa, on the border between Uganda and the Congo. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Guides on the summit of Mount Stanley (5,109 m). Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

One of the many waterfalls we encountered during the trek. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

The Frozen Bubbles

The lakes are starting to freeze in the Canadian Rockies, and the bubble craze (and skating season!) are just around the corner. I get a lot of emails in the winter about the methane bubbles that form under the ice, so I thought I’d provide a bit of info so more people can learn more about them.

The lakes are starting to freeze in the Canadian Rockies, and the bubble craze (and skating season!) are just around the corner. I get a lot of emails in the winter about the methane bubbles that form under the ice, so I thought I'd provide a bit of info so more people can learn more about them.

These bubbles can occur in many different lakes, and I have even shot the bubbles in 10-12 lakes in and around Banff National Park. However, the lakes eventually get snow-covered, and the majority of them will not show ice again until the spring when the bubbles are gone.

The bubble phenomenon occurs when the lakes are exposed to the warm Chinook winds causing some of the lakes to shed their snow to reveal the bubbles mid-winter. Some of the bigger lakes that come to mind are Abraham Lake, Lake Minnewanka, and Vermilion Lakes.

Locations:

Bubbles at the far end of Lake Minnewanka. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Abraham Lake is by far the most popular location to document the phenomenon as its surface is very easily accessible, and it gets far less snow than other parts of the Rockies. It's a busy place, though, when the bubbles do occur - people come from all over the world to shoot here, but if you're willing to walk/skate a little, you can find solitude still.

The Vermilion Lakes sometimes offer very short windows where the winds will blow the lakes free of snow and reveal small pockets of methane bubbles. Don't expect wide vast swaths of them, though.

Lake Minnewanka has the best bubbles I've ever seen, but they're often best at the far end of the lake, 20+ km from the road. For that reason, I expect it'll always be quiet there. If you are lucky, there are sometimes pockets of bubbles near the road too.

When to Shoot:

As far as when to shoot them, I've found that it can really depend. The window of opportunity is usually short, a few weeks at best. When we get a warm weather spell, like essentially all of last winter, then that window can narrow down to just a few days. Warm weather creates a film of water on the lakes, and the bubbles get "buried" deeper in the ice. I've found overall that the best time of the year to shoot them is mid-January to late February. Having said that, I got this image in November…

It goes without saying: Be safe, and always test the ice before getting into it!

Happy shooting out there, everyone. Might see you on the lakes this winter! More bubble photos are below!

Extreme Blues and Bobbing by Icebergs: Antarctica

This latest trip to Antarctica was one for the memory books, filled with its highs and lows (including 7-metre waves in the Drake Passage!) and inclement weather that finally gave way to an incredible experience: five hours riding zodiacs through Charlotte Bay to photograph whales, iceberg and epic scenery. I'm already missing the sense of remoteness, scale and grandeur.

This latest trip to Antarctica was one for the memory books, filled with its highs and lows (including 7-metre waves in the Drake Passage!) and inclement weather that finally gave way to an incredible experience: five hours riding zodiacs through Charlotte Bay to photograph whales, iceberg and epic scenery. I'm already missing the sense of remoteness, scale and grandeur.

I have 7,000 or so frames to go through but wanted to show you an initial set of images! Enjoy this window into the latest journey to the White Continent.

As always, all images are available as limited-edition prints in a variety of sizes and format.

Fur seals swimming in impossibly blue water. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Deception Island. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

A mammoth iceberg. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Moonrise over the Antarctic Peninsula. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Huge ice features. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Fur Seal on Deception Island. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Stunning details in icebergs. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Gentoo penguins at Dorian Bay. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Zodiac provides a sense of scale to the enormity of the landscape. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Peleno Strait. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Journey to the White Continent

It always seemed so unattainable to me. But after two days at sea, and a year of anticipation, I was mesmerized when we first caught sight of a few rocks off Elephant Island through the thick fog – harbingers of our imminent arrival on the fabled White Continent. There is no wilder place on Earth, nowhere more remote, more inhospitable.

Antarctica.

It always seemed so unattainable to me. But after two days at sea, and a year of anticipation, I was mesmerized when we first caught sight of a few rocks off Elephant Island through the thick fog – harbingers of our imminent arrival on the fabled White Continent. There is no wilder place on Earth, nowhere more remote, more inhospitable.

And as I found out over the six weeks following that moment in early January 2017, you’d be hard-pressed as a photographer to find another location on the planet that is more overwhelming. The photo opportunities just kept on coming, and I’ll never forget the sense of remoteness, the way life thrived on a whole other level, and the scale of the land down there. I’m thankful for One Ocean Expeditions for bringing me on board.

Amazingly, I managed to underestimate how many photographs I would take on the trip. When I returned home from the White Continent, the hard drives were filled to the brim, and between test shots, time-lapses, bracketed sequences and such, I came home with 40,000 files! I’m just starting to put a dent into all that material, but I would like to share some of the early results with you.

Antarctica is a place that will stay with me forever, and I very much look forward to revisiting my experience there through the thousands of photographs. I hope you enjoy the sneak peek!

The scale of South Georgia is absolutely overwhelming. Massive mountains grace the horizon. Glaciers are colossal. Penguins come by the thousands. Fur seals are everywhere you look. And the island itself is 2,000 km from the nearest mainland – isolation beyond description. I took this from our ship, the Vavilov, on an early morning at Gold Harbour, a place of incredible beauty. This is a penguin highway, which is simply a path of least resistance the animals continuously follow. In the back is the rapidly receding, spectacular Bertrab Glacier. By the way, the Canon 100-400 was by far my most used lens on the trip. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

I’ve taken my share of selfies, but never with penguins, fur seals and elephant seals looking on. That morning at St Andrews Bay was a highlight of the time spent on South Georgia with One Ocean Expeditions. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

A trio of synchronized whales swim into the endless Antarctica sunset. We saw dozens, perhaps hundreds of cetaceans that evening in the Gerlache Strait. The ice and mountains alone were just breathtaking. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

They had warned me that South Georgia would turn anyone into a wildlife photographer… Hard to ignore those three king penguins backlit by a fiery sunrise. This was at St Andrews Bay, meaning there were another 100,000 penguins right behind me. Just mind-blowing. I’d never seen life thrive at that level. This is the largest penguin colony on the island. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Love the mysterious, deep blue hues of Antarctic icebergs… Lemaire Channel, Antarctica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

This was one of the most entertaining wildlife encounters we had on South Georgia: a macaroni penguin and a blue-eyed shag fighting over a little rock island. I think I took 100 shots of that interaction, but with the subjects moving and the zodiac bobbing around on the waves, I never quite got the composition where I want it… This is the best one of the lot. A wonderful wildlife moment in the middle of nowhere. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

A self-portrait taken on Petermann Island on the Antarctic peninsula. Between the gentoo penguins, the huge icebergs floating by, and the distant glaciated peaks, this is one place I found particularly overwhelming as a photographer. Just incredible. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

As we explored the coast of the island that morning, we all did our best to simplify our compositions, usually by isolating one or two animals. But the truth is, South Georgia is an incredibly cluttered place. It’s a compositional mess of colours, textures and lines. So here’s a crowded image I feel is representative of that amazing island! A lot of the detail is lost here on social media but I hope it conveys a sense of the place. Fortuna Bay, South Georgia. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Ice in Antarctica comes in all shapes, sizes, textures and shades of blue. A paradise for the cryophile. The turquoise ramparts of this iceberg were particularly mesmerizing. Paradise Harbour, Antarctica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

I think it’s fair to say gentoo penguins look rather clumsy above the surface. Underwater though, they move with incredible speed and precision. I took 500 shots. A handful had penguins in them… Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Gloomy morning at Fortuna Bay, South Georgia. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Hiking on the peninsula, a sacred place. For me, every step was a privilege in that precious, stunning part of the world. In the background is the Conscripto Ortiz refuge, run by Argentina. Paradise Harbour, Antarctica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Camping on the 7th continent… Would you? I settled into my “moat” for the obligatory self-portrait and then realized the surroundings were just too good to pass up. I spent a sleepless, exhilarating, peaceful night exploring and photographing beautiful Leith Cove before returning to the ship. Leith Cove, Antarctica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Penguin life has its challenges. Gruesome, I know, but a reminder that leopard seals and other predators constantly prowl the icy waters of the Antarctic peninsula (good thing to keep in mind for the underwater photographer too I suppose). Danco Island, Antarctica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

I really wished I hadn’t used the word “epic” so much before going to Antarctica. I think we all ran out of superlatives soon after reaching the continent… Gerlache Strait, Antarctica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Brash ice, cirrus clouds and mammoth peaks – a perfect afternoon on the White Continent. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

An Adelie penguin reaches the extent of the sea ice, Antarctica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Self-portrait at the edge of the world. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

An albatross conveniently soars through the frame as crepuscular rays rain down on the peaks of South Georgia. So much beauty in that remote corner of the world. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Iceberg illuminated by the sun, Antartica. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

A lone Adelie penguin seemingly runs out of sea ice off of the Antarctic peninsula. As for us, we ran out of water. This encounter marked the southernmost extent of our journey: about 67 degrees, somewhere in Lallemand Fjord. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Journey Through the Torngat Mountains

The Torngats. The name alone evokes a sense of mystery. Tucked into one of the most remote parts of Canada lies one of the last frontiers for landscape photographers and explorers alike: the Torngat Mountains

The Torngats.

The name alone evokes a sense of mystery. Tucked into one of the most remote parts of Canada lies one of the last frontiers for landscape photographers and explorers alike: the Torngat Mountains. The area is an incredibly wild mix that fires up the imagination: Norway-like fjords, glacier remnants (and the associated turquoise lakes), a healthy polar bear population, jagged icebergs freshly arrived from Greenland, aurora-filled skies, cultural treasures, archeological gems, rich marine life, and some of the highest, most rugged peaks in all of Eastern Canada.

Best of all, all that incredible wilderness is now protected through the national parks system, and it is accessible to the adventurous-minded via the recently-established Torngats Base Camp.

It is a deeply sacred home to Inuit people and, back in August 2016, I had the incredible opportunity to spend a week in the area. It is truly amazing to be able to be among the first to document all that beauty with the camera. Not only that, but being able to do so in great comfort (especially given the remoteness). The facilities were top-notch, the local staff were most helpful and access to the landscape via zodiacs was as exciting as convenient.

The Torngats are truly a place you have to see for yourself. No words can do the place justice. It's like a modern-day Shangri-la, an overwhelming paradise for landscape and wildlife photographers. Even images don't get close to depicting what the Torngats are like, here's my attempt through my favourite images from the week!

→ All of these images are available as custom limited edition prints.

The Goose Bay area has great photos ops on the way up to the Torngats! Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

The Goose Bay area. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Unnamed Waterfall, Torngat Mountains, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Unnamed lake, Torngat Mountains, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Unnamed Waterfall, Torngat Mountains, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Aurora Harbour" 3 AM in the Torngats. The aurora borealis paints an incredible scene in the Labrador sky. Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

The aurora borealis paints an incredible scene in the Labrador sky. Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Aurora Borealis, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Moody day at Saglek Fjord, Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

North Arm, Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Even the local Parks staff never tire of the magic of the Torngats! Unnamed waterfall near North Arm, Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

A moment of bliss in the Torngats, sitting at the front of the boat, gazing out at the symmetry and the deep blue waters around us, and wondering what will lie around the next corner. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

North Arm, Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Sitting at the front of the boat, gazing out at the symmetry and the deep blue waters around us, and wondering what will lie around the next corner. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Torngats Glory" Just another beautiful, unnamed tumble of the Torngats. That morning it looked like Mother Nature has applied the "mosaic" filter to the reflections. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Big iceberg, bigger cliffs. Saglek Fjord, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"The Face" of SW Arm. Saglek Fjord, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

The Goose Bay area has great photos ops on the way up to the Torngats! Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Drying fish at Base Camp. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Northern Ramparts" The placid waters of the iconic Southwest Arm reflect an oil painting-like rendition of the cliffs towering above. The colourful wall rises nearly 1,000 metres above the fjord. It looks so much more impressive in person. :-) Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Welcome to the Torngats! Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

View over St. John's Harbour and Base Camp from "the inukshuk". Torngat Mountains, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Iceberg off shore, Torngat Mountains. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Northern Ramparts" The placid waters of the iconic Southwest Arm reflect an oil painting-like rendition of the cliffs towering above. The colourful wall rises nearly 1,000 metres above the fjord. It looks so much more impressive in person. :-) Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Morning at St. John's Harbour, right next to Base Camp. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Windex Lake as seen from the air. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Ramah Bay as seen from the air. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Rugged coastline of the Torngats as seen from the air. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Rugged coastline of the Torngats as seen from the air. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Nachvak Fjord from the air, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Labrador Magic." The incredible, raging Nakvak Falls, deep in Torngat Mountains National Park. This gem is reached either by flying or walking a looong way. I cheated for this one. There was only enough time for a few quick, safe shots, and off we went again! Thanks to pilot Steve for an incredible morning up high!

"Forgotten World." Of all the images I have posted from the Torngat Mountains National Park so far, this aerial view of the Southwest Arm is probably the one that is most representative of what the place is like. Part Norway, part Canadian Rockies, part Nunavut, yet unlike anywhere else I have gone before. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Aurora, noctilucent clouds and the first light of dawn paint an incredible scene in the Labrador sky. Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Self-portrait in Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Crayola Point." That is how we started referring to that 15-foot high lichen-covered spire. A bluebird day at that location really brings out the entire array of colours one finds in the Torngat Mountains. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Drifter... An underwater look at the fjords of Torngat Mountains National Park, complete with jellyfish. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Iceberg off the coast of the Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Warp Zone." Aurora over the abandoned, twisted Hudson Bay buildings of Hebron. The second I saw images of that remote, nearly deserted Moravian mission (only one family remains), I knew I wanted to photograph it at night. Big thanks to The Torngats Base Camp for getting me out there, and to bear guard Joe for working after hours and wandering around the site with me! Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Wild teetering iceberg, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

"Framed In Ice". Last light on the behemoths of the Labrador coast. These towers were approximately 30 metres high. I took a flurry of shots, trying to frame that little island as the light was fading and the boat was bobbing. Thankfully one of the frames worked out! Torngat Mountains, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Unnamed turquoise lake near North Arm, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Black Bear Tracks, Unnamed lake near North Arm, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Ramparts of the Southwest Arm, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Marine life, Torngat Mountains National Park. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

King of the hills. Large, healthy polar bear roaming among some of the world's oldest rocks. Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Large, healthy polar bear roaming among some of the world's oldest rocks. Torngat Mountains National Park, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Abandoned, twisted Hudson Bay buildings of Hebron, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Rooftop sunrise, Hebron Moravian mission, Labrador. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.

Watching the nearly-nightly aurora borealis display from my tent, Torngat Mountains Base Camp. Photo by Paul Zizka Photography.